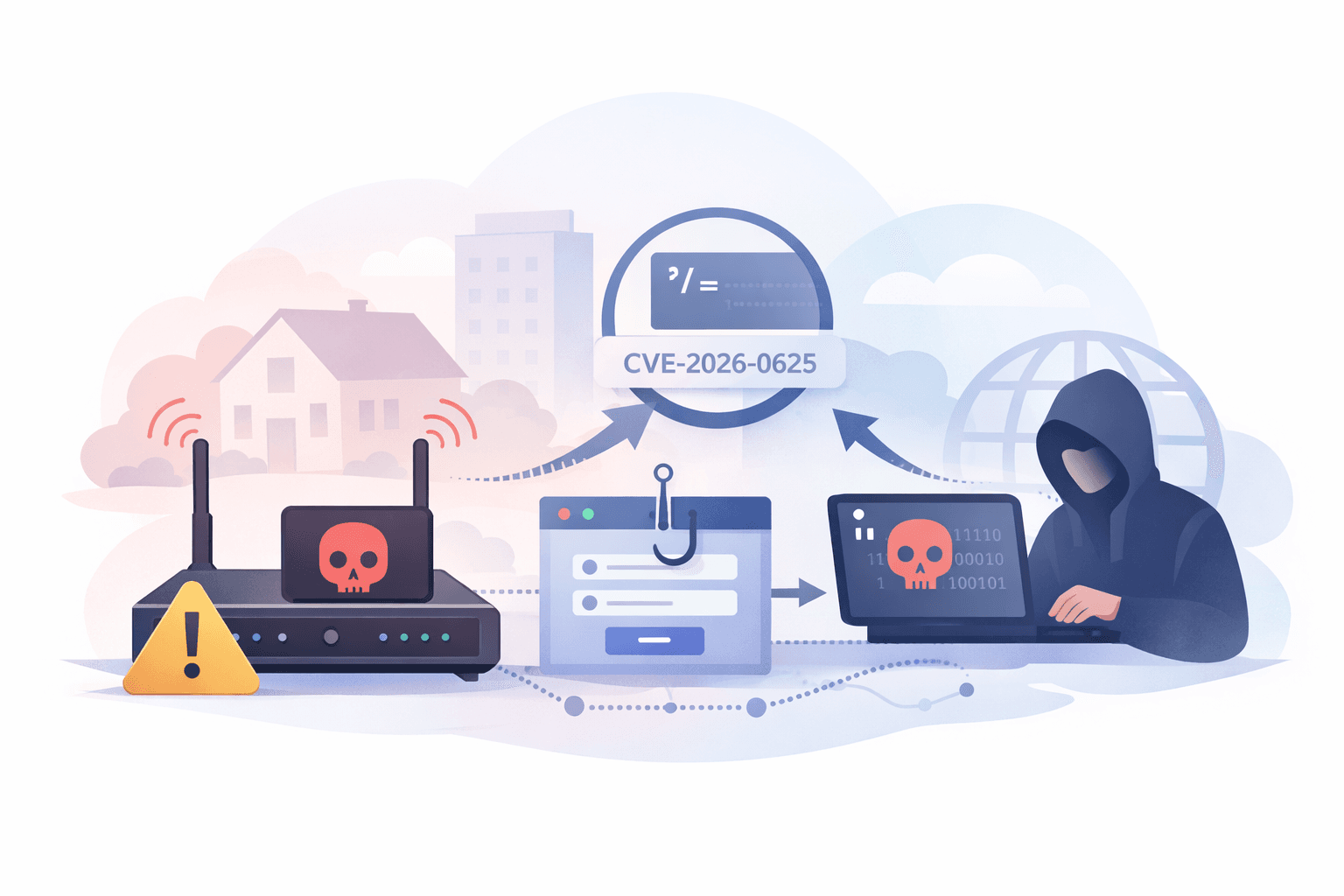

A newly disclosed zero-day vulnerability in legacy D-Link DSL routers has triggered urgent warnings from security researchers and the vendor itself. CVE-2026-0625, a critical command injection flaw with a CVSS v4.0 score of 9.3, allows unauthenticated attackers to execute arbitrary code remotely on vulnerable devices. The vulnerability affects multiple end-of-life router models that will never receive security patches, and active exploitation has already been detected by security monitoring platforms including Shadowserver Foundation honeypots.

The timing makes this discovery particularly concerning. These routers reached end-of-life around 2020, meaning thousands of devices remain deployed in homes and small businesses with no security updates for years. For IT administrators managing distributed networks or supporting remote users, the implications are severe: compromised edge devices can serve as persistent backdoors into internal infrastructure. This article examines the technical details of CVE-2026-0625, identifies affected hardware, analyzes real-world exploitation scenarios, and provides actionable remediation strategies for organizations dealing with legacy network equipment.

Understanding CVE-2026-0625: The Technical Vulnerability

The vulnerability resides in the dnscfg.cgi endpoint, a web-based configuration interface used for managing DNS settings on affected D-Link DSL gateway routers. The core issue stems from inadequate input validation and sanitization of user-supplied parameters.

The Command Injection Mechanism

When administrators configure DNS settings through the web interface, the router processes parameters without properly filtering shell metacharacters. Attackers can craft malicious HTTP requests containing specially formatted DNS configuration values that break out of the intended command context and execute arbitrary shell commands with root privileges.

The vulnerability requires no authentication because the affected CGI endpoint fails to enforce proper access controls before processing configuration requests. This design flaw transforms what should be an authenticated administrative function into an externally exploitable attack surface.

Observed and Potential Attack Vectors

Exploitation can occur through two primary pathways:

- Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF): Attackers embed malicious requests in web pages or emails. When a user on the same network visits the compromised content, their browser automatically sends the crafted request to the router's internal IP address.

- Direct remote access: Routers configured for remote administration expose the vulnerable endpoint directly to the internet, allowing attackers to exploit the flaw without requiring CSRF.

Important: While CSRF remains a feasible attack method within local networks, real-world exploitation observed by security researchers primarily involves direct remote attacks against exposed router interfaces.

Exploitation Consequences

Successful exploitation delivers several critical impacts:

- Complete device takeover with root-level access

- DNS hijacking to redirect traffic through attacker-controlled servers

- Network reconnaissance and lateral movement preparation

- Persistent backdoor installation for long-term access

- Man-in-the-middle attack staging

Table: CVE-2026-0625 Vulnerability Profile

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| CVE ID | CVE-2026-0625 |

| CVSS v4.0 Score | 9.3 (Critical) |

| Attack Vector | Network (CSRF or Direct) |

| Authentication Required | None |

| User Interaction | Required (CSRF) / Not Required (Direct) |

| Impact | Remote Code Execution, DNS Hijacking |

Affected Hardware and Detection Challenges

D-Link has confirmed that multiple legacy DSL router models contain the vulnerability, though the complete scope remains under investigation due to firmware variation across product lines.

Confirmed Vulnerable Models

The following models and firmware versions have been verified as vulnerable:

- DSL-526B: Firmware version 2.01 and earlier

- DSL-2640B: Firmware version 1.07 and earlier

- DSL-2740R: Firmware versions below 1.17

- DSL-2780B: Firmware version 1.01.14 and earlier

All confirmed models reached end-of-life status around 2020, meaning D-Link ceased providing firmware updates and security patches years ago. The manufacturer has explicitly stated these devices will not receive fixes for CVE-2026-0625.

Why Detection Is Complex

Both VulnCheck researchers and D-Link have emphasized that identifying all vulnerable devices presents significant challenges. Legacy D-Link routers shared common codebases and components across model lines, but firmware implementations diverged over time through regional customizations and OEM partnerships.

According to D-Link's security advisory, the company is manually validating firmware across both legacy and currently supported product platforms. This process revealed that model numbers alone cannot reliably determine vulnerability status—specific firmware versions, build variants, and regional customizations must be examined.

Identification Methods

Organizations can identify potentially vulnerable devices through several approaches:

- Direct device inspection: Log into router administrative interfaces and check model number and firmware version against confirmed vulnerable lists

- Network scanning: Use asset discovery tools to inventory all D-Link devices, then cross-reference against vulnerability databases

- Vendor communication: Contact D-Link support with device serial numbers for definitive vulnerability status

Pro Tip: Maintain an updated inventory of all network edge devices including routers, modems, and gateways. End-of-life dates should be tracked as part of hardware lifecycle management to prevent security debt accumulation.

Active Exploitation and Real-World Attack Patterns

Security researchers have confirmed that CVE-2026-0625 is not merely a theoretical vulnerability—attackers are actively exploiting it in the wild.

Observed Attack Activity

Global threat monitoring organizations, including the Shadowserver Foundation, have confirmed active exploitation attempts against vulnerable D-Link devices in the wild

These campaigns primarily involve automated internet-wide scanning and direct exploitation rather than user-interaction-based attacks targeting vulnerable D-Link routers. These observations indicate that exploit code is available to threat actors and being used in active campaigns.

The detection of honeypot activity typically suggests widespread scanning and exploitation attempts across the internet. Attackers often use automated tools to identify vulnerable devices at scale, then compromise them for various purposes.

Typical Attack Scenarios

Real-world exploitation of router vulnerabilities like CVE-2026-0625 follows predictable patterns:

Scenario 1: DNS Hijacking Campaign

Attackers compromise vulnerable routers and modify DNS settings to redirect users to malicious infrastructure. When users attempt to visit legitimate banking or e-commerce sites, they're instead directed to convincing phishing pages designed to harvest credentials. The router's privileged position in the network makes this particularly effective—users have no indication their traffic is being manipulated.

Scenario 2: Botnet Recruitment

Compromised routers are enrolled in botnets for distributed denial-of-service attacks, spam campaigns, or cryptocurrency mining. The relatively low computational power of individual routers is offset by the massive scale of vulnerable devices. End-of-life equipment is particularly attractive for this purpose because victims are less likely to notice performance degradation or update non-functional devices.

Scenario 3: Internal Network Pivot

Advanced persistent threat actors use compromised edge devices as initial footholds for network intrusion. Once inside the perimeter, attackers conduct reconnaissance, identify valuable targets, and move laterally to compromise additional systems. For remote workers using vulnerable home routers to access corporate resources, this scenario poses significant risk to enterprise security.

Table: Attack Timeline for Router Exploitation

| Phase | Duration | Attacker Activity | Defender Visibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reconnaissance | Minutes to hours | Network scanning, vulnerability identification | Low (appears as normal traffic) |

| Initial Exploit | Seconds | Command injection, code execution | Low to none |

| Persistence | Minutes | Backdoor installation, configuration modification | Very low |

| Post-Exploitation | Days to months | Data collection, lateral movement, malicious operations | Varies by attacker sophistication |

Why Legacy Devices Are Prime Targets

End-of-life networking equipment represents the perfect target for attackers. These devices combine widespread deployment with guaranteed lack of security updates. Once a vulnerability is disclosed in EoL hardware, the attack surface is permanent—devices become progressively more vulnerable as new exploitation techniques emerge and exploit code proliferates.

How do organizations typically discover their routers have been compromised? Often through secondary indicators: unexplained network performance issues, reports of phishing pages from users, or alerts from security tools detecting malicious DNS resolutions. Direct detection of router compromise is difficult without dedicated monitoring.

Remediation Strategies and Risk Mitigation

D-Link's official guidance is unambiguous: affected routers should be retired and replaced. However, organizations must often manage the gap between ideal security posture and operational constraints.

Primary Recommendation: Hardware Replacement

The only comprehensive solution for CVE-2026-0625 is replacing vulnerable devices with actively supported models. Modern routers from reputable manufacturers typically receive firmware updates for 5-7 years after release, and many now support automatic update mechanisms.

When selecting replacement hardware, prioritize devices with:

- Active vendor support and documented update policies

- Automatic firmware update capabilities

- Strong security track records from independent researchers

- Enterprise-grade features like VLAN support and logging

Interim Mitigation Measures

Organizations unable to immediately replace vulnerable devices should implement defense-in-depth strategies to reduce risk:

Network Segmentation

Isolate vulnerable routers on dedicated network segments with minimal access to critical infrastructure. Use firewall rules to restrict communication between the compromised segment and sensitive systems.

Disable Remote Administration

Ensure administrative interfaces are only accessible from the local network. Disable UPnP, remote management, and any cloud-based management features that could expose the device to external attacks.

DNS Configuration Hardening

Where possible, override router DNS settings at the client level. Configure workstations and servers to use trusted public DNS resolvers (like Cloudflare's 1.1.1.1 or Google's 8.8.8.8) rather than relying on router-provided DNS.

Enhanced Monitoring

Implement network monitoring to detect anomalous behavior:

- Monitor DNS query patterns for suspicious resolutions

- Track outbound connections from the router's IP address

- Alert on configuration changes to network equipment

- Log and review all administrative access attempts

Table: Mitigation Strategy Effectiveness

| Strategy | Risk Reduction | Implementation Complexity | Ongoing Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware Replacement | 100% | Medium | Low |

| Network Segmentation | 60-70% | Medium to High | Medium |

| Disable Remote Access | 40-50% | Low | Low |

| DNS Override | 30-40% | Low | Low |

| Enhanced Monitoring | 20-30% (detection only) | High | High |

Organizational Policy Considerations

This incident highlights the importance of proactive hardware lifecycle management. Organizations should establish policies that address:

- Maximum deployment lifetime for network edge devices

- Quarterly reviews of vendor end-of-life announcements

- Budget allocation for emergency security replacements

- Testing procedures for firmware updates before deployment

- Asset inventory processes that track security support status

Important: The true cost of maintaining end-of-life equipment extends far beyond the hardware purchase price. Factor in the security risk, potential incident response costs, and time spent managing workarounds when making retention decisions.

Broader Implications for Legacy Network Equipment

The CVE-2026-0625 disclosure serves as a case study in the systemic challenges of aging network infrastructure, particularly in environments where hardware decisions are decentralized or underfunded.

The Growing EoL Security Problem

Consumer and small business networking equipment typically has a shorter support lifecycle than enterprise hardware, yet often remains in production far longer. Home users may operate the same router for a decade or more, while small businesses squeeze extended value from aging equipment to control costs.

This creates an expanding attack surface as devices transition from supported to obsolete. Vulnerability researchers continue finding flaws in old firmware, but vendors have no economic incentive to patch products they no longer sell. The result is a growing population of permanently vulnerable devices.

Supply Chain Security Dimensions

Many organizations have limited visibility into the network equipment used by remote workers, contractors, or acquired companies. These "shadow IT" devices can introduce vulnerabilities that bypass enterprise security controls. When remote users connect to corporate resources through compromised home routers, they potentially expose sensitive data or provide attacker pivot points.

IT teams should assess whether remote access policies adequately address the security posture of user home networks. Is VPN required for all corporate resource access? Are there network-level controls to limit the blast radius if a remote user's home network is compromised?

Vendor Responsibility and Market Dynamics

The networking industry lacks standardized support lifecycle commitments comparable to those found in enterprise software. Some manufacturers provide security updates for years after discontinuing products; others abandon devices shortly after end-of-sale. This inconsistency makes informed purchasing decisions difficult for consumers and IT professionals alike.

What mechanisms could improve this situation? Regulatory approaches like the EU Cyber Resilience Act are beginning to mandate minimum support periods for connected devices. Industry self-regulation through security standards and vendor transparency about support commitments would also help.

Key Takeaways

- CVE-2026-0625 represents a critical, unpatchable vulnerability in multiple legacy D-Link DSL routers that have been actively exploited by attackers

- The command injection flaw requires no authentication and enables complete device compromise, DNS hijacking, and use as a network intrusion foothold

- Affected models reached end-of-life around 2020 and will never receive security patches, making replacement the only complete remediation

- Organizations must implement network segmentation, disable remote administration, and enhance monitoring if immediate hardware replacement is not feasible

- Maintaining an inventory of network edge devices with tracked end-of-life dates is essential for proactive security management and preventing the accumulation of permanently vulnerable equipment

Conclusion

CVE-2026-0625 exemplifies the critical security risks inherent in operating end-of-life network equipment. The combination of a severe vulnerability, active exploitation, and the impossibility of patching creates an untenable security position for any organization operating affected D-Link routers. Interim mitigations can reduce risk exposure but do not eliminate the vulnerability. Complete risk removal is only achieved through permanent device replacement.

The broader lesson extends beyond this specific vulnerability. As networking equipment ages beyond vendor support windows, each newly disclosed flaw becomes a permanent addition to the attack surface. IT teams must balance the operational costs of hardware replacement against the compounding security risks of extended deployment. For critical infrastructure like edge routers—which mediate all network traffic and control access to internal resources—erring on the side of proactive replacement is the prudent choice.

Organizations should use this incident as a catalyst to review their hardware lifecycle management practices and ensure that security support status is a primary factor in retention decisions. The question is not whether legacy devices will be compromised, but when—and whether you'll have visibility and controls in place to limit the damage.

Given the confirmed active exploitation and permanent lack of vendor support, continued operation of affected routers represents an unbounded and compounding security risk that should be treated as a critical infrastructure liability.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can I protect my vulnerable D-Link router by changing the admin password or disabling remote access?

A: Changing the admin password does not protect against CVE-2026-0625 because the vulnerability requires no authentication. Disabling remote administration reduces risk by limiting attack vectors to CSRF-based exploitation from the local network, but does not eliminate the vulnerability. The only complete solution is replacing the device with supported hardware.

Q: How can I tell if my D-Link router has already been compromised?

A: Signs of compromise include unexpected DNS configuration changes, unfamiliar devices in connected client lists, unexplained performance degradation, or users reporting being redirected to suspicious websites. However, sophisticated attackers may leave no obvious traces. If you have a vulnerable model, assume compromise is possible and implement monitoring or replace the device immediately.

Q: Are other D-Link router models beyond those specifically named also vulnerable?

A: Possibly yes, depending on firmware lineage and regional builds. However, at present only the listed DSL models have been formally confirmed as affected by this specific CVE.

Q: If I must continue using a vulnerable router temporarily, what's the most important mitigation step?

A: Disable all remote administration features and ensure the router's web interface is only accessible from the local network. This forces attackers to use CSRF-based attacks, which require user interaction and are easier to prevent through security awareness and browser protections. Also, immediately plan for hardware replacement within the shortest timeframe your budget allows.

Q: Does using a VPN or firewall behind the vulnerable router provide adequate protection?

A: No. While a VPN encrypts traffic leaving your network and a firewall can control inbound connections, neither protects against the router itself being compromised. A compromised router can intercept traffic before encryption, modify DNS responses, or serve as a persistent backdoor into your network. Defense-in-depth layers help but cannot substitute for removing the vulnerable device from your infrastructure.